2.1 Nicotine

Part A - Interim decisions on matters referred to an expert advisory committee (November 2016)

2. Joint meeting of the Advisory Committee on Chemicals and Medicines Scheduling (ACCS-ACMS #14)

2.1 Nicotine

On this page: Referred scheduling proposal | Current scheduling status and relevant scheduling history | Relevant scheduling history | Scheduling application | Australian regulatory information | International regulations | Substance summary | Pre-meeting public submissions | Summary of Joint ACCS-ACMS advice to the delegates | Delegates' considerations | Delegates' interim decision

Referred scheduling proposal

An applicant has proposed to exempt nicotine from Schedule 7 at concentrations of 3.6 per cent or less of nicotine for self-administration with an electronic nicotine delivery system ('personal vaporiser' or 'electronic cigarette') for the purpose of tobacco harm reduction.

Current scheduling status and relevant scheduling history

Nicotine is currently listed in the Poisons Standard in Schedules 7, 6 and 4, Appendix F (Part 3), and Appendix J (Part 2) as follows:

Schedule 7

NICOTINE except:

- when included in Schedule 6;

- in preparations for human therapeutic use; or

- in tobacco prepared and packed for smoking.

Schedule 6

NICOTINE in preparations containing 3 per cent or less of nicotine when labelled and packed for the treatment of animals.

Schedule 4

NICOTINE in preparations for human therapeutic use except for use as an aid in withdrawal from tobacco smoking in preparations for oromucosal or transdermal use.

Appendix F, Part 3 (POISONS (other than agricultural and veterinary chemicals) TO BE LABELLED WITH WARNING STATEMENTS OR SAFETY DIRECTIONS) under the entry:

NICOTINE except when in tobacco

Safety directions 1: Avoid contact with eyes, and 4: Avoid contact with skin.

Appendix J, Part 2

NICOTINE: 1 - Not to be available except to authorised or licensed persons.

Relevant scheduling history

In June 1991, the Drugs and Poisons Schedule Standing committee (DPSSC) amended the Schedule 4 entry for nicotine to include all preparations (except Schedule 3 chewing tablets) which could be used as an aid in smoking cessation, containing between 2 and 4 mg of nicotine or roll-on devices with 0.65 per cent or less of nicotine e.g. transdermal patches.

In August 1993, the National Drugs and Poisons Schedule committee (NDPSC) rejected a proposal to have 2 mg sublingual tablets rescheduled from Schedule 3 to Schedule 2 and 4 mg sublingual tablets rescheduled from Schedule 4 to Schedule 3.

In November 1993, the NDPSC agreed that Schedule 4 remained appropriate for patch formulations. Subsequently, in November 1997, transdermal patches were included in Schedule 3.

In February 1997, the NDPSC rescheduled nicotine 2 mg chewable tablets to Schedule 2. However, committee decided that the higher dosage (4 mg) should only be rescheduled to Schedule 3 to facilitate the counselling of heavy smokers by a pharmacist.

In August 1998, the NDPSC agreed to the inclusion of nicotine gum and transdermal patches in Appendix H.

In November 1998, the NDPSC considered down-scheduling nicotine for inhalation, when packed in cartridges for use as an aid in withdrawal from tobacco smoking, from Schedule 4 to Schedule 3 and decided that Schedule 3 was appropriate. The NDPSC noted that this form of oral inhalation was similar in many respects to the chewing gum, being absorbed mainly in the mouth and throat. The data provided indicated that nicotine plasma levels obtained via the inhaler were similar to those obtained with the 2 mg chewing gum.

In February 1999, the NDPSC amended this Schedule 3 nicotine entry to 'Nicotine as an aid in withdrawal from tobacco smoking in preparations for inhalation or sublingual use'. In August 2001, the NDPSC agreed that nicotine lozenges would have a comparable safety profile to that of sublingual tablets, and so it was appropriate to also include lozenges in Schedule 3. Subsequently, lozenge-preparations were down scheduled to Schedule 2 in June 2003. In February 2002, nicotine inhalers were rescheduled from Schedule 3 to Schedule 2.

In February 2010, the NDPSC considered an application to broaden the exemptions for specified NRT buccal dosage formats i.e. chewing gum and lozenges, to buccal preparations in general. The NDPSC decided to only down-schedule oromucosal sprays and did not support an exemption for oromucosal preparations in general, noting that this could potentially include preparations such as mouthwashes. The NDPSC was of the opinion that there was insufficient data for such a broad exemption.

In June 2010, the NDPSC considered a post-meeting submission regarding the February 2010 decision to exempt nicotine preparations for oral mucosal spray use from scheduling. The committee confirmed the February 2010 resolution (2010/58-20) to amend the scheduling of nicotine to exempt oromucosal spray use as an aid in withdrawal from tobacco smoking. The committee agreed that this decision should be referred to a delegate under the new scheduling arrangements commencing 1 July 2010 for consideration of inclusion into the first instrument under these new arrangements with an implementation date of 1 September 2010.

In June 2011, the ACMS considered a proposal to amend the Schedule 4 entry to exempt from scheduling when used for human therapeutic use as an aid in withdrawal from tobacco smoking: (i) nicotine oromucosal film; and (ii) nicotine inhalation cartridges for oromucosal use. These proposed exemptions were similar to the exemptions for nicotine in chewing gums, lozenges, and preparations for sublingual, transdermal or oromucosal spray use when used as an aid in withdrawal from tobacco smoking.

ACMS advised that the Schedule 4 exemption for nicotine in preparations for human therapeutic use be extended to include all oromucosal use and include a definition for oromucosal in the Poisons Standard Part 1, Interpretation. The committee advised and the delegate agreed with the deletion of the Schedule 2 nicotine entry (i.e. all nicotine inhalation cartridge preparations for oromucosal use as aids in withdrawal from tobacco smoking would become exempt with any other inhalation preparations for human therapeutic use being captured by Schedule 4). Further, the delegate extended the scheduling exemption for nicotine in preparations for human therapeutic use to include all oromucosal use (to harmonise with the New Zealand scheduling of nicotine for human therapeutic use). The decisions were implemented on 1 January 2012.

Scheduling application

This was a general application. The applicant's proposed amendments to the Poisons Standard are as follows:

Schedule 7 - Proposed amendment

NICOTINE except:

- when included in Schedule 6;

- in preparations for human therapeutic use; or

- in tobacco prepared and packed for smoking; or

- in preparations for use as a substitute for tobacco when packed and labelled:

- for use in an electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS)

- nicotine concentration up to 3.6%

- maximum nicotine per container: 900 mg

- in a child resistant container

- labelled with the concentration of nicotine and other ingredients

- labelled with the statement 'Keep out of reach of children'

- labelled with the statement 'Not to be sold to a person under the age of 18 years'.

The applicant's reasons for the request are as follows:

- Harm reduction is a well-documented strategy to reduce the harm of behaviour by substituting it with a less harmful behaviour. Tobacco harm reduction provides an alternative pathway for smokers who are unable or unwilling to quit nicotine. Tobacco harm reduction has huge potential to prevent death and disability from tobacco and reduce health inequalities.

- The scheduling of nicotine was considered by the National Drugs and Poisons committee (NDPSC) in October 2008. The proposed amendment was to exclude nicotine from Schedule 7 'in electronic cigarettes prepared and packed as an alternative to traditional smoking'. The committee agreed that the current scheduling remained appropriate and that the Schedule 7 parent entry for nicotine should remain unchanged (NDPSC Oct 2008).

- The applicant asserts since that earlier consideration there has been considerable development in the public health understanding, smoker adoption and regulation of these products globally. This application will update the committee on these developments, with the conclusion that the scheduling of nicotine in Australia for non-therapeutic purposes should be amended.

Australian regulatory information

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) are also known as e-cigarettes, personal vaporisers, and vape pens. Nicotine for human consumption is listed in Schedule 4 in the Poisons Standard, except when used as an aid in the withdrawal from tobacco smoking in preparations intended for oromucosal or transdermal use (e.g. nicotine patches, gum or mouth sprays). Nicotine is in Schedule 7, except in preparations for human therapeutic use or in tobacco prepared and packed for smoking. There are no restrictions on importation, but individuals may commit an offence under state and territory laws when they take possession of, or use, imported nicotine.

In the states and territories, it is an offence to manufacture, sell or supply nicotine as Schedule 7 poison without a licence or specific authorisation. This means e-cigarettes containing nicotine cannot be sold in any Australian state or territory. Nicotine can be imported by an individual for use as an unapproved therapeutic good (e.g. a smoking cessation aid), but the importer must hold a prescription from an Australian registered medical practitioner and only import not more than 3 months' supply at any one time. The total quantity imported in a 12-month period cannot exceed 15 months' supply of the product at the maximum dose recommended by the manufacturer. The purchase and possession of nicotine by individuals are not regulated by Commonwealth legislation, except for importation as allowed under Commonwealth law.

Non-nicotine e-cigarettes are currently not regulated as a therapeutic good under the Commonwealth Therapeutic Goods Act. To date, none have been approved by the TGA for registration as a medical device.

In April 2015, the Commonwealth Department of Health engaged the University of Sydney (in partnership with the Cancer Council New South Wales) to explore options to minimise the risks associated with the marketing and use of ENDS in Australia. The project was initiated under the auspices of the Intergovernmental committee on Drugs (IGCD) which reports to the Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council Mental Health, Drug and Alcohol Principal committee. The IGCD nominated that the Department of Health act as the lead agency to oversee the project.

The outcomes of the project are to inform policy options for ENDS (with or without nicotine) that may be considered separately or in coordination by the Commonwealth, state and territory governments. The project is due to report in mid-2016. The Tobacco Control Policy Section has indicated that the report is imminent. However, the broader dissemination of the report will be a matter for the IGCD. At this time it is unknown when the IGCD will be meeting to discuss this report.

International regulations

UK: The 2016 UK guidance policy on regulation of e-cigarettes is available through the following link https://www.gov.uk/guidance/e-cigarettes-regulations-for-consumer-products.

NZ: In August 2016, the NZ Ministry of Health released a consultation document (pdf,431kb), considering policy options for the regulation of electronic cigarettes and agreeing in principle to allowing the sale of nicotine e-cigarettes as a consumer product.

USA: The USA National Institute on Drug Abuse includes information on e-cigarettes at https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/electronic-cigarettes-e-cigarettes.

Information on the US FDA ruling on e-cigarettes is available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm499234.htm and US FDA labelling information on vaporisers, e-cigarettes and ENDS is at http://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/labeling/productsingredientscomponents/ucm456610.htm

Substance summary

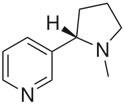

Nicotine (Figure 2.1) is a liquid alkaloid obtained from the dried leaves of the tobacco plant, Nicotiana tabacum and related species (Solanaceae). Tobacco leaves contain 0.5 to 8% of nicotine combined as malate or citrate. Nicotine is a colourless or brownish, volatile, hygroscopic, viscous liquid. Soluble in water and; miscible with dehydrated alcohol.

Figure 2.1: Structure of nicotine

| Property | Nicotine |

|---|---|

| CAS No. | 54-11-5 |

| Chemical name | 3-[(2S)-1-Methylpyrrolidin-2-yl]pyridine |

| Molecular formula | C10H14N2 |

| Molecular Weight | 162.2 g/mol |

When smoked, nicotine is distilled from burning tobacco and carried on tar droplets (particulate matter), which are inhaled. Nicotine has a plasma half-life of approximately 2 hours. It is metabolised in the liver primarily by the CYP2A6 enzyme into cotinine which is excreted by the kidneys. Nicotine used in nicotine solutions for e-cigarettes is extracted from tobacco leaves.

The toxicity of other ingredients inhaled in solutions used in e-cigarettes was not addressed in this application. The Applicant states that other chemicals in e-cigarette vapour include volatile organic compounds, carbonyls, aldehydes, tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) and metal particles.

Pre-meeting public submissions

Of the 71 public submissions received, 54 supported and 17 opposed the proposal.

The 54 submissions in support of the proposal were from consumers (35), business owners or manufactures (6), peak bodies (2), advocacy groups (3), medical professionals (7) and a consultant (1).

The main points supporting the proposal were as follows:

- Personal accounts of quitting tobacco or reduced nicotine intake with positive health benefits using e-liquids containing nicotine when other nicotine therapies were unsuccessful or experienced side effects.

- International evidence that e-cigarettes reduce smoking and help smokers quit smoking. Consider that e-cigarettes work because they are pleasurable and address both the nicotine and habit aspect of smoking.

- Consumers can access harm reduction measures. Vaping is less harmful than smoking and is a significant harm reducer for smokers. Nicotine in ENDS, may contain small amounts of other chemicals including volatile organic compounds, carbonyls, aldehydes, tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) and metal particles. However, research indicates that they are present at much lower levels than in cigarette smoke. Use of ENDS reduces toxin intake.

- Nicotine is already approved in gums, lozenges, patches, inhalers and cigarettes.

- The current laws are confusing and mixed in Australia. Although the use of nicotine in vaping solutions is illegal, it is commonplace. Consumers struggle to understand why nicotine is hard to obtain, given cigarettes are easy to obtain. Suggest decriminalising possession of e-liquid nicotine, making it a consumer product at strength applied for in the application with availability through responsible retailers. By decriminalising, the risk associated with grey and black market unregulated supply chain would be mitigated.

- Consumers are concerned about importing products from overseas, the uncertainty of these products, the restrictions and breaking laws if vaping and potentially driving vaping consumers back to smoking as it is easier to go to the nearest store and obtain cigarettes.

- Consumers including minors can currently obtain e-liquid containing nicotine online from overseas, without responsible retailing to sell the products to adult consumers. Those without internet access and those uncomfortable with buying online are excluded from a harm reduction strategy which has been very successful for many people. As "disadvantaged groups in the population are more likely to take up and continue smoking" (Trends in the prevalence of smoking by socio-economic status), the very people who could be most helped by having low-strength nicotine available are those least likely to be able to access it.

- Suggestions were provided that these should have correct labelling displaying relevant consumer information and warnings relating to use e.g. unsuitability for pregnant and breast feeding women.

- The UK Royal College of Physicians report Nicotine Without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction (pdf,3.61Mb) states 'A risk-averse, precautionary approach to e-cigarette regulation can be proposed as a means of minimizing the risk of avoidable harm, e.g. exposure to toxins in e-cigarette vapour, renormalisation, gateway progression to smoking, or other real or potential risks. However, if this approach also makes e-cigarettes less easily accessible, less palatable or acceptable, more expensive, less consumer friendly or pharmacologically less effective, or inhibits innovation and development of new and improved products, then it causes harm by perpetuating smoking.' The UK Royal College of Physicians have stated that vaping is at "least" 95% safer than smoking and recommend doctors advising patients to switch to vaping.

- The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (pdf,200kb) Article 1(d) states: "tobacco control" means a range of supply, demand and harm reduction strategies that aim to improve the health of a population by eliminating or reducing their consumption of tobacco products and exposure to tobacco smoke; it seems that Australia is not fulfilling its FCTC obligations in providing access to the harm reduction strategies outlined in article 1(d).

- ENDS are available in New Zealand. Expected changes in New Zealand which would legalise availability of nicotine-containing e-liquids would likely create a problem with illicit product importation if Australia's regulations do not change. Consideration should be given to the emerging regulatory framework for e-cigarettes in New Zealand.

- Overseas these products are sold OTC - overseas research (UK) indicates that the majority of vapers are in ex-smokers and only 0.3% of never smokers used e-cigarettes in 2015 (similar to nicotine replacement therapy 0.1%). Public Health England has endorsed vaping as safer than smoking. Australia should harmonise with the UK and USA and NZ.

- In France, the High Council on Public Health has endorsed electronic cigarettes as a cessation tool.

- In Belgium the Superior Health Council has stated that electronic cigarettes are a less harmful alternative to tobacco (a position subsequently endorsed by the Health Ministry).

- In normal conditions of use, toxin levels in inhaled ENDS aerosol are below prescribed limit values for occupational exposure, in which case significant long-term harm is unlikely.

- Lethal overdose of nicotine is rare as nicotine is an emetic and any ingestion of liquid nicotine diluent, such as that used for ENDS would result in vomiting.

- Nicotine is the main psychoactive agent in tobacco, it has relatively minor health effects. It is not a carcinogen, does not cause respiratory disease and has only minor cardiovascular effects.

- Regarding the uptake of "vaping" in previously non-smoking youth, the available evidence does not support the "gateway hypothesis" that ENDS encourages nicotine addiction or uptake by youth. In the UK, daily ENDS use in youth is almost exclusively confined to those who already use combustible tobacco daily and regularly. Less than 0.2% of youth who have never smoked combustible tobacco have taken up vaping and there is no evidence of progression to smoking in this cohort.

- Abuse in children: as almost all minors who have used an e-cigarette with nicotinated e-liquid had also tried at least one cigarette. States that the majority of US youth who use vaporisers and e-cigarettes do not vape nicotine.

- Nicotine dependence in youth develops rapidly and over 50% of those youth who smoke daily are already nicotine dependent. Young people who are already smoking can reduce their harm by switching to ENDS by 95%, as was shown in the Public Health UK Report.

- Low concentration nicotine has a proven safety record and is currently widely available as Nicotine Replacement Therapy. The proposed low concentrations present no significant risks. Low risks can be mitigated by packaging and labelling requirements.

- Anti-tobacco restrictions should not be extrapolated to low concentration nicotine use.

- Many health professionals believe that the health risk of consuming nicotine in low dosages (as per electronic cigarettes) is about as harmful to your health as drinking a cup of coffee.

- One user has found the sweet flavours satisfy urges to eat sugary foods.

- No quantifiable harm for those in the vicinity of those vaping. Regarding second hand exposure concerns, at the Public Health UK report included that passive exposure to vapour have generally concluded that the risk to bystanders is very small and that Public Health England found that "ENDS release negligible levels of nicotine into ambient air with no health risks to bystanders".

- Australia's smoking rates amongst socially disadvantaged groups, particularly people with mental illness have remained unacceptably high. In the US, over 40% of tobacco sales are to people with a mental illness and this figure has been estimated to be even higher in Australia. Most of the 25-year mortality gap between people with schizophrenia and the general population is directly attributable to smoking. People with mental illness smoke in much higher rates than the general population, and the poor health outcomes reported in research are typically associated with smoking related harms. People with mental illness should be offered the opportunity to reduce or quit smoking using e-cigarettes. Existing nicotine replacement therapies have very poor efficacy and they are often costly, not at all affordable for people on a disability pension. E-cigarettes by comparison are very low cost, which increases the likelihood of their uptake by this population.

- Liquid nicotine should be supplied to agreed specifications in Australia by an accredited manufacturer and dispensed by an accredited Australian pharmacist. This would ensure a range of safeguards in regard to the supply and quality of nicotine in Australia.

- In regard to the Personal Importation Scheme, the TGA website states "such therapeutic goods may not be approved for supply in Australia, and this means there are no guarantees about their safety or quality." Considers that this is an untenable situation in regard to a substance like liquid nicotine given emerging trends in e-cigarette use, vaping and smoking cessation considerations in Australia.

- There is a strong public health, ethical and pragmatic case to amend the schedule and to allow Australians access to much less risky ways to consume nicotine than smoking.

- Scientific evidence suggests negative effects of use in the long term are unlikely - significant drops (similar to cold turkey quitters) in biomarkers of smokers who switched to vaping. Stable, long term improvements in asthma symptoms have been found in smokers who switch to electronic cigarettes which demonstrate a significant level of harm reversal.

- The 3.6% is on the conservative side, some experts recommend stronger doses when attempting to quit nicotine altogether.

- Nicotine Quickmist® can be purchased at supermarkets and deliver 1 mg of nicotine per spray and each can has 150 sprays. These can be bought easily by anyone (even young adults).

- Nicotine toxicity has been much misconceived in both popular press and general community perception, and even in some scientific sectors, with a lethal dose often quoted to be as little as 60 mg. Bernd Mayer[1] provides an historical perspective of this misconception, and provides a summary of research including clinical trials on animals, as well as investigations into inadvertent and intentional overdoses, and concludes that a careful estimate of the LD50 for nicotine is 0.5 g, or 6.5 mg/kg, which for the 36 mg/mL concentration proposed for approval, is theoretically approximately 15mL. But this would be almost impossible to reach the bloodstream in its entirety, due to the severe vomiting and diarrhoea such a dose would immediately arouse. Most recorded suicide attempts using nicotine have failed for this reason, with little or no long term effects.

- Vapers self-regulate nicotine dosage like smokers using tobacco products by reducing or stopping puffs taken on the basis of early symptoms of overdose such as headache, dizziness and nausea.

- Legalising nicotine-containing electronic cigarettes will make their manufacture, presentation and sale safer for consumers by:

- reducing consumers' dependence on the unlawful or black market products proliferating in Australia.

- shaping a regulatory regime ensuring that all products on the market comply with appropriate standards of quality and safety

- The costs associated with listing nicotine vaping products on the ARTG is a disincentive to manufacturers to pursue with option of nicotine delivery.

- While the possession of nicotine solution remains illegal, there is no consumer regulation of these products - products are mislabelled to reduce detection. Current policy drives low-dose nicotine users underground, to obtain supplies from overseas or from merchants who do not label the nicotine content of the vaping fluid.

- Tax on e-cigarettes overseas is low compared to traditional cigarettes, this is incentive to switch

- ENDS has a 50-70% success rate of quitting tobacco smoking while having positive health effects on the body.

- Nicotine solution of 3.6% or less is also not enough product to cause a deadly result from ingestion as it takes 500-1000mg of pure Nicotine for death and the concentration level is too low.

- We should be making it easier, not harder, for people to access products that might help them quit, and provide more options.

- Potential for harm outweighs the potential for abuse.

- One supporting submission also proposed a 3% allowance for animal use, moving it from Schedule 6 (Poison) to Schedule 5 (Caution) together with a Schedule 5 entry for nicotine in preparations containing 3.6% or less of nicotine when labelled and packed for use in e-cigarettes (electronic nicotine delivery systems or ENDS) on the basis that at the 3.6% level of dilution it should be used with caution, but it was not considered a dangerous poison.

The 17 submissions that do not support the proposal were from academia (1), Government Health Departments (7), non-government organisations (4) and peak bodies (5).

The main points opposing the proposal were as follows:

- The risks and benefits of the use of a substance

- Given that nicotine is readily absorbed through the skin, nicotine available in liquid form for use in e-cigarettes poses a significant risk of acute nicotine poisoning. Furthermore, there is serious risk of acute nicotine poisoning for children which can occur through ingestion of products containing nicotine. There has been evidence of this internationally in the USA and UK.

- The safety and long term health effects of these products are unknown, and any potential benefits are still to be determined and may be outweighed by the risks posed by their widespread use in the community.

- The limited evidence to indicate that electronic cigarettes are effective nicotine cessation aids does not justify the risks posed by these products.

- Research has shown that most people who use electronic cigarettes do not quit smoking conventional tobacco products, resulting in dual-use. Dual use results in a much smaller benefit on overall survival compared to quitting smoking entirely.

- The chemical combinations used in electronic cigarettes have adverse impacts on pulmonary function and the cardiovascular system.

- Second-hand e-cigarette vapour contains pollutants at levels above background levels and therefore is associated with negative health effects.

- Nicotine is highly addictive. Permitting nicotine as an ingredient in e-cigarettes increases the risk of individuals, who would have otherwise been unlikely to become tobacco smokers, developing nicotine addiction.

- The inherent risk of promoting ENDS as an option for smoking harm reduction follows the massive failures of past harm reduction interventions such as cigarette filters and 'light' and 'mild' product descriptors.

- Through heavy marketing and advertising strategies, there is a possibility that smoking may once again become socially acceptable.

- The purposes for which a substance is to be used and the extent of use of a substance

- There is limited and highly conflicting evidence internationally regarding the effectiveness of using e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid (with or without nicotine). This research is in its infancy with some research groups stating that smokers who used e-cigs were less likely to quit smoking tobacco than those who did not,[2] while others state that e-cigarettes helped smokers to stop smoking tobacco long term and reduce the amount smoked by half.[3]

- Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council and the World Health Organization (WHO) does not currently consider e-cigarettes to be a legitimate tobacco cessation therapy as 'no rigorous peer-reviewed studies have been conducted to show that e-cigarettes are a safe, effective, Nicotine Replacement Therapy.

- Availability of alternative smoking cessation aids, such as nicotine replacement therapies (e.g. gum and patches), have been rigorously assessed for efficacy and safety and have been approved by the TGA. However, e-cigarettes may be more attractive to smokers than existing nicotine replacement products, due to their lower cost, mimicry of the smoking action and potential better nicotine delivery system. These factors may discourage smokers from quitting.

- E-cigarettes containing nicotine may be marketed as a way to improve social status rather than for smoking cessation, which may increase the appeal of the product to non-tobacco-smoking youth.

- The extent of use of e-cigarettes containing nicotine is at the discretion of the user, which may increase the incidence of nicotine addiction and nicotine poisoning.

- Once a thorough assessment has been completed into the safety and efficacy of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid, these products should be restricted to prescription only.

- Evidence suggests that e-cigarettes undermine the intent of smoke-free laws, as many smokers use non-nicotine e-cigarettes in legislated smoke-free areas to maintain their smoking behaviour.

- The toxicity of a substance

- Nicotine is highly toxic and poses a number of health hazards including adverse cardiovascular, respiratory, renal and reproductive effects. Despite the lower dose proposed, effects on cardiovascular system and the risk of developing cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are nearly as large as smoking traditional tobacco products.

- Nicotine can be absorbed through the skin and poisoning may result in symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, seizures, abdominal pain, fluid build-up in the airways (bronchorrhea), high blood pressure, ataxia, rapid heart rate, headache, dizziness, confusion, agitation, restlessness, neuromuscular blockade, respiratory failure and death (with large doses - medium lethal dose 6.5-13 mg/kg).

- Evidence from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (the WHO’s source for information about cancer) suggests that nicotine is associated with DNA damage and other pathways of carcinogenesis.

- Human and animal data suggest that nicotine exposure during periods of developmental vulnerability (foetal through adolescent stages) has multiple adverse health consequences, including impaired foetal brain and lung development, and altered development of cerebral cortex and hippocampus in adolescents, which may result have future mental health implications for the exposed child.

- The claim that 'ENDS are 95% less harmful than smoking' was derived from the guesses of a consensus group (whose provenance has been heavily questioned), rather than from an appropriately conducted and peer-reviewed, scientific research study.

- The dosage, formulation, labelling, packaging and presentation of a substance

- The wide variation in available devices and cartridge fluids make it difficult to quantify the safety of all e-cigarettes.

- Exemption from scheduling may mean there will be less control over standards and quality control of preparations, labelling and packaging considerations and the application of warning statements.

- There is a lack of evidence to support a safe dose. Some submitters suggest that the proposed 3.6% is too high. This concentration equates to approximately 36 mg of nicotine per ml of liquid, in comparison to the 13-30 mg of nicotine in a single cigarette. Furthermore, the dosage of nicotine administered through an e-cigarette, and frequency of use, is largely at the discretion of the user. These factors may lead to an increased incidence of addiction and poisoning, especially in children.

- Labelling

- It is important that health risks of nicotine be clearly labelled and that the packaging be childproof and not be designed to appeal to young people.

- Some a-liquids that do not list nicotine on the label have been found, upon scientific testing by State and Territory health authorities, to contain nicotine. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has recently commenced proceedings in the Federal Court against two a-cigarette retailers alleging false or misleading representations and misleading conduct by making statements on their websites that their ENDS products did not contain toxic chemicals

- Formulation

- Allowing open access to ENDS nicotine supplies will result in large-scale respiratory exposure to thousands of e-cigarette additives (such as propylene glycol, glycerol, ethylene glycol and flavourings) which have never been assessed for safety via inhalation in aerosol form (whether directly of via second-hand vapour).

- When heated, one of the common e-cigarette additives, propylene glycol, can form the carcinogenic derivative propylene oxide.

- Flavoured e-cigarettes (e.g. bubble gum, fruit and confectionary flavours), with or without nicotine content, could appeal to adolescents (leading to rapid uptake of tobacco smoking) and to children (leading to toxicity).

- Device safety

- There are concerns regarding device safety and a growing amount of global evidence to suggest that ENDs devices carry a risk of battery failure, low-quality materials, manufacturing flaws and malfunction, leading in some cases to explosions, fire and injury.

- The potential for abuse of a substance

- The practice of 'vaping' a high volume of liquid in order to produce the biggest or most intricate cloud of vapour also creates a risk of inadvertent nicotine poisoning if the e-cigarette used contains nicotine.

- Any other matters that the Secretary considers necessary to protect public health

- Personal Importation Scheme: A process already exists for individuals to import personal vaporisers and/or liquid nicotine for personal therapeutic use via the TGA's Personal Importation Scheme.

- Gateway to relapse: Risk of gateway to relapse. There is a risk that former tobacco smokers and nicotine addicts may relapse through the use of e-cigarettes containing nicotine.

- Gateway to tobacco use (in adults and adolescents):

- International evidence from the USA and UK, indicate that e-cigarettes (regardless of nicotine content) are being used by individuals as a gateway to tobacco use, triggering a new generation of smokers. There is a concern that advertising e-cigarettes will serve to reverse much of the progress that has been made to de-normalise, de-glamorise and reduce tobacco smoking in Australia.

- There has been a rapid increase in the number of adolescents using e-cigarettes in the USA and UK. In the UK, 20% of British youths (aged 11-15) have used e-cigarettes, 73% of whom are non-smokers. This has been associated with higher incidences of users transitioning onto traditional cigarettes. The US stats indicate that e-cigarette use has increased four-fold in middle and high schoolers from 2011-2012 and that the continual fall in cigarette smoking that has been occurring since at least 1998, stopped in 2014 and 2015.

- Industry bias:

- The argument that nicotine is all but benign is often advanced by those highly conflicted by commercial interests involved in selling ENDS. Such arguments seldom note the findings of a large body of research into possible adverse effects arising from consumption of nicotine.

- The long term business model for the ENDS industry must involve seeing cohorts of young people take up vaping, regardless of protests from that industry to the contrary. In the UK where it is illegal to sell ENDS supplies to children, a recent report[4] found that 40% of ENDS retailers did so.

Summary of Joint ACCS-ACMS advice to the delegates

The committee advised that the current scheduling of nicotine remains appropriate.

The matters under subsection 52E (1) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 considered relevant by the Committee included: a) the risks and benefits of the use of a substance; b) the purposes for which a substance is to be used and the extent of use of a substance; c) the toxicity of a substance; d) the dosage, formulation, labelling, packaging and presentation of a substance; e) the potential for abuse of a substance; f) any other matters that the Secretary considers necessary to protect the public health.

The reasons for the advice comprised the following:

- There is a risk of nicotine dependence associated with use of Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS). The potential for nicotine dependence is much higher with third generation ENDS and is greater than with the nicotine replacement therapy products marketed in Australia. In countries such as the USA where there has been more ready access to ENDS there is some evidence that ENDS use in never-smoking youth may increase the risk of subsequent initiation of cigarettes and other combustible products during the transition to adulthood when the purchase of tobacco products becomes legal. There is some dual use of conventional cigarettes and ENDS in smokers. There is a risk that ENDS will have a negative impact on tobacco control and may re-normalise smoking. If exempt from Schedule 7, availability of ENDS in children may cause an increase in smoking as they transition to adulthood, which raises public health concerns.

- There is little evidence regarding the safety of long term nicotine exposure via ENDS. Exposure to nicotine in adolescents may have long-term consequences for brain development, potentially leading to learning and anxiety disorders. The toxicity of long term exposure to nicotine delivered by ENDS is unknown. Long-term exposure to excipients via the ENDS route of exposure is uncertain.

- Nicotine can cause nausea, vomiting, convulsions, bronchorrhoea, high blood pressure, ataxia, tachycardia, headache, dizziness, confusion, agitation, restlessness, neuromuscular blockade, respiratory failure and death in overdose.

- The proposed maximum amount of 900 mg of nicotine per pack is within the estimated lower limit causing fatal outcome (500 mg to 1g). There have been reports of unintentional ingestion of ENDS liquid by children with severe outcomes in some cases. The proposed maximum concentration of 36 mg of nicotine per mL is high (the EU Tobacco Product Directive specifies a maximum concentration of 20 mg/mL). The amount of nicotine in 5 mL of a 3.6% solution in ENDS is 180 mg, which would likely cause significant toxicity in a young child (5 mL would be one swallow for a toddler). Child-resistant packaging would reduce the risk of unintentional exposure to the solution in children.

- ENDS is used for Tobacco Harm Reduction, assistance with cessation of smoking and for recreational use. Public health authorities have varying views about the benefits of ENDS to tobacco harm reduction and as an aid in smoking cessation. Currently about 9% of current smokers and recent quitters in Australia use ENDS. Excepting nicotine from Schedule 7 would likely result in increased nicotine exposure via ENDS (based on countries such as the UK and USA where these products are more widely available, and the increase in Australia in recent years). In the UK 19% of smokers and 8% of ex-smokers currently use ENDS.

- The use of a label warning statement 'not to be sold to a person under the age of 18 years' is not likely to be effective unless there is enforcement of this requirement. There is a risk there will be inappropriate marketing and advertising of nicotine for use with ENDS if nicotine for use with ENDS is exempted from Schedule 7.

Delegates' considerations

The delegates considered the following in regards to this proposal:

- Scheduling proposal

- Joint ACCS-ACMS advice

- Public submissions received

- Section 52E of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989;

- Scheduling Policy Framework (SPF 2015)

- Other relevant information.

Delegates' interim decision

The delegates' interim decision is the current scheduling of nicotine remains appropriate.

The delegates considered the relevant matters under section 52E (1) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989: a) the risks and benefits of the use of a substance; b) the purposes for which a substance is to be used and the extent of use of a substance; c) the toxicity of a substance; d) the dosage, formulation, labelling, packaging and presentation of a substance; e) the potential for abuse of a substance; f) any other matters that the Secretary considers necessary to protect the public health.

The reasons for the interim decision are the following:

- The delegates acknowledge and agree with the ACCS-ACMS advice.

- There is a risk of nicotine dependence associated with use of Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS). The potential for nicotine dependence is much higher with third generation ENDS and is greater than with the nicotine replacement therapy products marketed in Australia. In countries such as the USA where there has been more ready access to ENDS there is some evidence that ENDS use in never-smoking youth may increase the risk of subsequent initiation of cigarettes and other combustible products during the transition to adulthood when the purchase of tobacco products becomes legal. There is some dual use of conventional cigarettes and ENDS in smokers. There are several published studies showing that youth who initiate smoking with e-cigarettes are about three times more likely to be smoking conventional cigarettes a year later. There is a risk that ENDS will have a negative impact on tobacco control and may re-normalise smoking. If exempt from Schedule 7, availability of ENDS in children may cause an increase in smoking as they transition to adulthood, which raises public health concerns.

- There is little evidence regarding the safety of long term nicotine exposure via ENDS. Exposure to nicotine in adolescents may have long-term consequences for brain development, potentially leading to learning and anxiety disorders. The toxicity of long term exposure to nicotine delivered by ENDS is unknown. Long-term exposure to excipients via the ENDS route of exposure is uncertain.

- Nicotine can cause nausea, vomiting, convulsions, bronchorrhoea, high blood pressure, ataxia, tachycardia, headache, dizziness, confusion, agitation, restlessness, neuromuscular blockade, respiratory failure and death in overdose.

- The dosage, formulation, labelling, packaging and presentation of the nicotine as would occur if the scheduling was amended would allow nicotine to be too accessible as a liquid which has higher risks and requires appropriate controls.

- The proposed maximum amount of 900 mg of nicotine per pack is within the estimated lower limit causing fatal outcome (500 mg to 1g). There have been reports of unintentional ingestion of ENDS liquid by children with severe outcomes in some cases. The proposed maximum concentration of 36 mg of nicotine per mL is high (the EU Tobacco Product Directive specifies a maximum concentration of 20 mg/mL). The amount of nicotine in 5 mL of a 3.6% solution in ENDS is 180 mg, which would likely cause significant toxicity in a young child (5 mL would be one swallow for a toddler). Child-resistant packaging would reduce the risk of unintentional exposure to the solution in children.

- In the USA, accidental poisonings associated with e-cigarettes have increased from one per month in 2010 to 215 per month in 2014 including one death.

- ENDS is used for Tobacco Harm Reduction, assistance with cessation of smoking and for recreational use. Public health authorities have varying views about the benefits of ENDS to tobacco harm reduction and as an aid in smoking cessation. Currently about 9% of current smokers and recent quitters in Australia use ENDS. Excepting nicotine from Schedule 7 would likely result in increased nicotine exposure via ENDS (based on countries such as the UK and USA where these products are more widely available, and the increase in Australia in recent years). In the UK 19% of smokers and 8% of ex-smokers currently use ENDS.

- The use of a label warning statement ‘not to be sold to a person under the age of 18 years’ is not likely to be effective unless there is enforcement of this requirement. There is a risk there will be inappropriate marketing and advertising of nicotine for use with ENDS if nicotine for use with ENDS is exempted from Schedule 7.

Footnotes

- Bernd Mayer. How much nicotine kills a human? Tracing back the generally accepted lethal dose to dubious self-experiments in the nineteenth century. Arch Toxicol. 2014; 88(1): 5–7

- Grana et al. 'E-cigarettes: A Scientific review' Circulation. 2014, 129(19), 1972-1986

- McRobbie et al. 'Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation (Review)' Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016, 9, CD010216

- Retailers 'flout' laws on selling e-cigarettes to children